Founding History

This is an early history of the Utility Workers Union of America. Its not a scholarly dissertation, replete with minute detail and documentation, nor is it intended to be. Instead it is more of a light and airy ride in a free balloon from which we will look down occasionally upon the landscape when something draws our interest, and if we look closely we are bound to see and recognize the faces of some of those who went before and upon whose shoulders the union now stands.

This is an early history of the Utility Workers Union of America. Its not a scholarly dissertation, replete with minute detail and documentation, nor is it intended to be. Instead it is more of a light and airy ride in a free balloon from which we will look down occasionally upon the landscape when something draws our interest, and if we look closely we are bound to see and recognize the faces of some of those who went before and upon whose shoulders the union now stands.

The history of the UWUA is full of bright spots, victories, and a few defeats, and it goes back further than most of us do. This unfortunately creates a problem of appreciation, especially of the early years. How does one recreate the texture of those times? How can we feel now that which was felt then? What was it like to practice unionism in the mid-1930’s? Whether you feel it was more rewarding or less rewarding, more difficult or less difficult than now, it was, in any case, far different from that which you experience today.

Oh, for the Good Old Days!

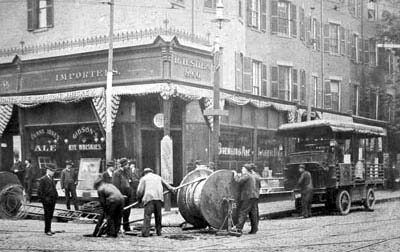

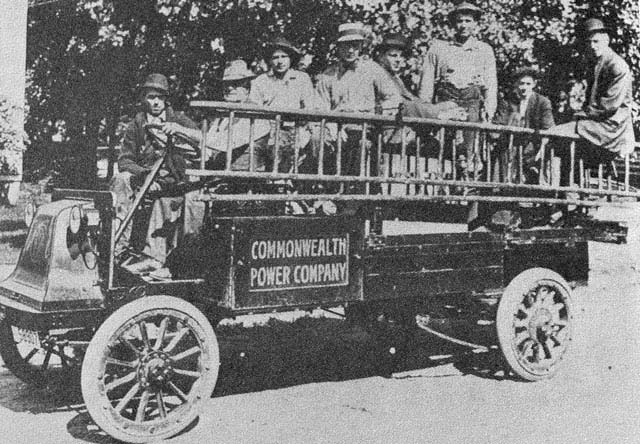

In those early years, the slenderest of roots of the UWUA could be found embedded in the soil in many parts of the U.S. In New York, Michigan, Pennsylvania, California and Ohio, to name only a few locations. It was a time that was not at all friendly to unionization. In fact, quite the contrary. The employers, industrialists, moguls, call them what you wish, were appalled at the thought of an organized work force. Employment at will was the commonest form of contract, which of course was no contract at all. The workman was considered as a kind of raw material from which a product was made. He was paid a meager slice of the profits gained from that which he produced. “Produced” is a key word here. Being sick and unable to work resulted in loss of pay; after all, there was nothing produced. And of course, major illness equated to major non-production and was tantamount to discharge.

Other aspects of the workman’s employment also help to gain insight into his societal position. One did not grieve a work assignment, one accepted it. One did not complain about an unsafe condition, one tried to avoid it. And most certainly, one did not demand a wage increase, one hoped for it. To complain about such conditions was considered rebellious and unforgivable behavior, to join a group protesting conditions was another way of saying “I’m about to look for another job.” To actually lead a protest effort was considered akin to armed assault. Those who did, seldom heard the five o’clock whistle blow. And so it went.

Suffice to say, the workman’s lot was a dreary one. He lived a mere existence and dared not hope for a brighter future. That what you now consider indispensable was then unobtainable. He was truly cast in the role of the raw material that fueled the engine of production. Most frightening of all was that for many years, society found no quarrel with this state of affairs. It was this climate of intimidation, fear, and lack of concern for the employee with which the early union organizers were forced to contend.

The Winds of Change

But in the early 1930’s, the winds of change were starting to blow. Society was beginning to suspect that this one-sided employee/employer relationship was not a healthy one. Pressure for some kind of parity began to mount. Pressure that demanded a meaningful change in this industrial relationship.

On June 16, 1933, Section 7(a) of the National Recovery Act became effective amid tremendous acclaim from workers. This section simply said:

Employees shall have the right to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and shall be free from interference, restraint, or coercion of employers of labor, or of their agents, in the organization or in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid protection.

This was a bare minimum, but none the less a tremendous advantage. A crescendo of union activity followed the passage of the NRA, and of course it drove the employers crazy. They simply couldn’t abide the loss of their cherished master-servant relationship. They said it would lead to industrial anarchy. It didn’t. They said it would destroy the industrial capacity. It didn’t. They predicted many dire consequences would occur, but they didn’t. In sum, they said it wouldn’t work, but it did. However, one thing they didn’t say was that they were willing to sink to any depth to prevent the law from becoming a reality. They ushered in an era of beatings, goon squads, armed guards, tear gas, shootings, and other genteel forms of combat. It got so bad that it caused Congress, in 1935, to pass a bill sponsored by Senator Robert Wagner, liberal Democrat from New York, which underwrote labor’s right to organize free from intimidation and coercion, and voiced support for collective bargaining as a matter of national policy. This of course was the National Labor Relations Act. Popularly called the “Wagner Act.”

Employers opposed it in Congress and in the courts. They sought to evade it, by-pass it, or refuse, as long as they could, to comply. They took it to the Supreme Court on the basis of its constitutionality and in 1937, in a five to four decision in NLRB vs. Jones and Laughlin, the court said:

Employees have as clear a right to organize and select their representatives for lawful purposes, as the respondent has to organize its business and select its own officers and agents. …Long ago, we stated the reason for labor organizations. We said that they were organized out of the necessity of the situation; that a single employee was helpless in dealing with an employer; that he was dependent ordinarily on his daily wage for the maintenance of himself and his family; that if the employer refused to pay him the wages he thought fair, he was nevertheless unable to leave the employ and resist arbitrary and unfair treatment; that union was essential to give laborers opportunity to deal on equality with their employer…

Even this did not entirely stay their hand. But you know that, don’t you. To this day, these aborigines, or their sons, are still out there.

Everybody Needs a Union

As we begin to unfold our early history, it is of singular importance to recognize that about the time our local organizations were beginning to form, so also was the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) aborning. This fact is important in that the CIO was the structure upon which the beginning of the UWUA was pinned.

For purposes of our narrative, we cannot justify a long pause to discuss the massive history resulting from the birth of the CIO, but we must at least brush against these beginnings as we pass to give context and form to our organizational foundation.

In this truncated version, we will begin with an already established American Federation of Labor and note only that organizational efforts by this body were conducted along traditional craft lines, a fact that was decried by a number of their member organizations. The vocal leader of this minority was John L. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers, who was joined in this minority by Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, Charles Howard of the Typographical Union, David Dubinsky of the International Ladies Garment Workers, Thomas McMahon of the United Textile Workers, Harvey Flemming of the Oil, Gas, and Refinery Workers, Max Zaritsky of the Hatters, Calp and Millinery, and Thomas Brown of the Mine, Mill and Smelters, all of whom believed that there was a need and a future in the organization of industrial workers. To this end, they pressed for and succeeded in creating a Committee for Industrial Organization within the AFL, and they first announced the founding in the Sunday papers of November 9, 1935.

A short time later, in a radio speech broadcast in early 1936, Lewis explained the organizational hopes of this new committee.

These millions of workers in our mass production industries have a right to membership in effective labor organizations and to the enjoyment of industrial freedom. They are entitled to a place in the American economic sunlight. If the labor movement and American democracy are to endure, these workers should have the opportunity to support their families under conditions of health, decency, and comfort; to own their own homes; to educate their children; and to possess sufficient leisure to take part in wholesome social and political activities. How much more security we would have in this country for the future of our form of government if we had a virile labor movement that represented, not merely a cross-section of skilled workers, but also represented the men who work with their hands in our great industries, regardless of their trade or calling!

It is for the purpose of enabling them to acquire and enjoy these rights that eight international unions of the American Federation of Labor…have formed the Committee for Industrial Organization…We are working for a future labor movement which will assure a proper future for America—one which will crystallize the best aspirations of those who really wish to serve democracy and humanity.

This new committee took it upon themselves to organize the industrial worker, but soon found themselves in a violent dispute with William Greene, president of the AFL, who announced the reaction of the AFL Executive Council, describing the movement as “dual unionism” and called upon the CIO unions to disband. They refused and continued their efforts in a now hostile environment. In spite of this, soon this new idea, this new committee, was to become a new organization, the “CIO.”

Although this committee assumed the mantle of an educational group promoting industrial unionism within the AFL, soon the initials “CIO” began to take on a magic of their own with workers of the mass production industries who were in rebellion against the old way of industrial life. They were sick of low pay, arbitrary firings, and speed-ups. They wanted industrial unions, and the CIO began to successfully assist their organizational efforts. That these efforts were clearly successful is witnessed by the fact that millions became organized under the CIO banner.

Enter the C.I.O.

But the old hostilities regarding dual-unionism did not go away. The AFL first suspended the AFL-affiliated unions that had stayed with the CIO; and then, in early 1938 these unions were expelled. November of that same year, the CIO met in Pittsburgh and changing one word of the original name formed the “Congress of Industrial Organizations,” with John L. Lewis the first president, and Philip Murray and Sidney Hillman the vice presidents.

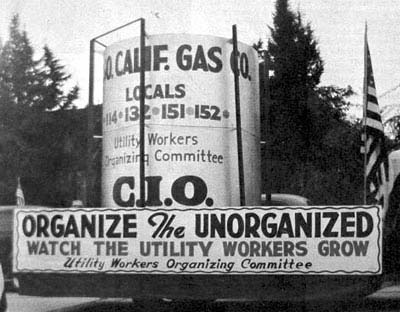

Vice President Murray immediately set about establishing the Utility Workers Organizing Committee (UWOC) within the CIO, assumed the chairmanship and appointed Albert Stonkus to be the organizing director. A few short months later, in the latter part of September, Lewis called Alan Haywood, then president of the New York State Council CIO, to a meeting in a New York hotel and offered him the chairmanship of this newly formed committee. Haywood accepted the job and soon after his acceptance, Stonkus decided to resign. Thus, in November of the same year that he took the assignment, Haywood found himself the chairman of an institution heavily in debt and directorless. After struggling along for a full year with the committee that was barely afloat, he was assigned the additional burden of its directorship.

It was then, in late November of 1939, that Chairman/Director Haywood decided it was time to go to the Washington Headquarters of the CIO and request the right to hire some people to do the organizing work. The leadership, impressed with his enthusiasm, gave him the go-ahead. Thus armed, he set about his search for people who had the ability, talent, and the desire to put together a union organization. It is here that we meet the men and hear the names we have heard many times since. There was Harold Straub and Ed Shedlock from New York; Reggie Brown from Pennsylvania; Garland Sanders from Michigan; and Bill Munger from Ohio.

These men set about the hard, grueling, sometimes dangerous, exciting task of organizing the unorganized under the banner of the UWOC. By 1939, after hopscotching the country coast to coast, they could report 39 new unions organized. By 1940, the figure rose to 42, to 96 in 1941, and nearly doubled in 1942 to a count of 180 local unions. It might be surprising to some to know that not all these locals represented utility workers, some locals represented workers with railroad systems. In fact, of the 180 unions in the UWOC fold in 1942, 79 of them were railroad locals.

My Boss, My President, My Friend

We now leave the UWOC for a moment and turn our attention to the development of our local unions. However, before doing this we should take note of the one wild shot most used by many employers in their frenzy to avoid legitimate unionization.

One of the earliest ploys attempted by management to keep unions at bay was a variation of the theme “if you can’t beat um, join um.”

They went about setting up their own unions; nice, wholesome, company dominated, and of course, tame organizations, that at least gave an illusion of independence, and it worked for a while. But even the dullest began to get suspicious when monthly union meetings were held in the company Board of Directors room. Even more destructive to their clever plan was that many people were far from dull and began to recognize these early set-ups as raw material out of which could be fashioned real representative organizations. Also about this time, the government saw how silly this all was becoming and said “Come on fellas, pick a side; you’re either management or you’re not!” And with that we said “Goodbye” to company unions (at least formally).

Here and There We Struggle to Our Feet

It is at this point, if we hope to follow the beginnings of the UWUA, we are forced to run off in many directions at the same time. The risk is to exclude any number of interesting stories about the early history of a number of our local unions, but as was said at the onset this is but an overview, much too condensed to permit such multiple digressions. However, we will examine a few specific cases of local union development, either because a number of our early leaders came from these locals and/or because their formation is interesting and documentation is readily available. We apologize in advance if your local is not included. The aforementioned time, space, and lack of documentation make such omissions understandable, if not excusable.

Consumers Power (There Auto Be a Better Way)

As you will soon see, most of the utility employers tried to start company unions with the forlorn hope that such organizations would in some way prevent honest unionism from gaining a toe-hold on their properties. Consumers Power Company was not an exception but their efforts (intended or otherwise) seemed half-hearted and a bit late. In fact, they found themselves actually competing with real efforts resulting from strong interests in union principles developing in the minds of employees at Saginaw, Bay City, and Flint, Michigan. Garland Sanders, a lineman with the company, was astute enough to perceive this interest and accepted the task of building upon this interest a strong formal union organization. It wasn’t long before he felt his efforts were ready to pay off, that he had what it took, and he was right, for suddenly Consumer’s Power was a company with a real union, a union affiliated with the CIO. Not long after that, the union had its first contract with the company; a contract between Consumers Power Company and, well, you’ll never guess who! A contract that was signed by the United Auto Workers. The reason for this rather unusual relationship was that the UAW was the only established union close by capable of absorbing this fledgling.

As you will soon see, most of the utility employers tried to start company unions with the forlorn hope that such organizations would in some way prevent honest unionism from gaining a toe-hold on their properties. Consumers Power Company was not an exception but their efforts (intended or otherwise) seemed half-hearted and a bit late. In fact, they found themselves actually competing with real efforts resulting from strong interests in union principles developing in the minds of employees at Saginaw, Bay City, and Flint, Michigan. Garland Sanders, a lineman with the company, was astute enough to perceive this interest and accepted the task of building upon this interest a strong formal union organization. It wasn’t long before he felt his efforts were ready to pay off, that he had what it took, and he was right, for suddenly Consumer’s Power was a company with a real union, a union affiliated with the CIO. Not long after that, the union had its first contract with the company; a contract between Consumers Power Company and, well, you’ll never guess who! A contract that was signed by the United Auto Workers. The reason for this rather unusual relationship was that the UAW was the only established union close by capable of absorbing this fledgling.

When this first contract expired (and there is reason to believe that this was the very first contract entered into by any current local of the UWUA), John L. Lewis, then head of the CIO, thought it inappropriate for utility workers to be affiliated with the UAW and cast about for a more suitable relationship. Not much was available, but he did notice that there was a “United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers of America” in the CIO, and in that they had the word “electrical” in their title he figured, why not, and with that the Consumers Local was affiliated with the UE.

About this time, the IBEW came hustling into town (or they were hiding in the bushes all along) and at the conclusion of this latest contract they snapped up the Consumers group and signed a multi-year contract that provided less than three cents over its term. Needless to say, the members were irate – no, mad; well, more like boiling – and when the contract expired, the first chance they got, they headed for the exit. Here suddenly was an opportunity for the Consumer group and the UWOC to effect a mutually beneficial relationship.

The members needed qualified representation and the Utility Workers Organizing Committee needed members. Harold Straub and Ed Shedlock arrived on the scene and after many meetings and discussions, the membership cast their lot with the UWOC. With this act, they were to become the first chartered local in our family of locals. The local number “101” attests to this fact. Other locals at Consumers Power also have low numbers: Locals 103, 104, 105, 106 and 107. Such numbers indicate that many of the Consumers employees were the first to enter the UWUA.

Consolidated Edison (As Easy as 1-2)

Around this same time, unionism in an independent form was beginning to take hold in New York. An affiliation of the Bronx Gas and Electric Company, Yonkers Electric Light and Power, and the Westchester Lighting Company had by the mid-1930’s been operating a form of company union under the title of “Employees’ Representation Plan” wherein employee representatives for each of the enfolded groups were selected for the purpose of raising problems of mutual interest, and offering in the form of requests, solutions to these problems as is expressed in a portion of the old minutes produced below:

The purpose of this meeting is to form a group as outlined below, to discuss problems of mutual interest appertaining to the Yonkers, Bronx and Westchester Companies, and to present requests, when recognized as a bargaining group, to the Management.

After a discussion, it was decided to have the following plan of organization:

The Unit shall consist of the chairman, secretary and an advisory board, consisting of two members, of each general council of the Westchester Lighting Co., the Bronx Gas & Electric Co., and the Yonkers Electric Light & Power Co.

The chairmen, only, are to have the right to vote on all matters brought up for discussion and presentation to the Management.

In order to adhere to the principles of collective bargaining, the Unit must be accepted by each individual general council and then the Management will be requested to recognize the Unit as an official bargaining group.

The advisory board, in each case, shall consist of two members of comparable departments of each company’s general council, alternately attending each meeting of the Unit by groups (or departments) as agreed upon at each preceding meeting. It was decided at this meeting that two representatives of the Commercial Group (or department) of each general council would attend the next meeting in the capacity of advisory boards with the respective chairman and secretary of each council.

Such arrangements changed from time to time in form and content but the intentions remained the same, at least on the part of the employee representatives, to affect favorably the working conditions of the employees.

However, these attempts by the employees were, as was almost always the case, fatally flawed by the proviso that all decisions on merit, or actions taken on proposals, were the exclusive purview of management, as was reflected in the May 9, 1935, minutes of the Employees General Council:

We were informed that one of the major subjects presented for Company approval by the First General Council was the matter of job reclassification. This request was not granted by the Management and the First General Council suggested that we give this matter some thought and endeavor to have same favorably accepted by the Management. A motion was brought up to the effect that each representative, with the aid of a committee appointed from the members of his particular group, classify the jobs under his jurisdiction. This motion was seconded, voted upon and passed.

On March 23, 1936, the Public Service Commission approved a merger of the New York Edison Company, the Bronx Gas and Electric Company, the New Amsterdam Company, the Central Union Gas Co., the Northern Union Gas Co., and others into the “Consolidated Edison Company.”

Shortly after the forming of this new company, the Employees’ Representative Council met and affirmed its relationship with this new entity but the days of this company union were fast drawing to a close.

A year after the merger in April and May of 1937, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), an AFL affiliate, moved in and obtained a “Consent Recognition” to represent the ConEd employees. Thus, without options, the employees became members of the IBEW. The IBEW immediately issued charters to the seven company unions. Two charters were issued to ConEd locals (later to be Local 1-2 of the UWUA). The third went to the New York Steam Employees, the fourth to Consolidated Telegraph & Electrical Subway Employees, the fifth to New York and Queens Electric Light and Power, the sixth to Brooklyn Edison Company, and the seventh to two Westchester affiliates.

The members were far from happy with their new union inasmuch as the IBEW chartered them as “B” locals. This “B” local designation meant that these members could not perform work that IBEW reserved for its “A” members. This also meant that the IBEW was not going to last long at ConEd, and it didn’t.

In early 1940, a massive work jurisdiction dispute erupted on the ConEd property when the IBEW insisted that stranger “A” members be brought in to do work normally assigned to ConEd workers. The membership was furious, but the IBEW didn’t care. What to do? They went on strike and with this action the IBEW gobbled up their treasury. This was the last straw and the seven “B” locals threw the IBEW out. They demanded of the National Labor Relations Board that an election be held. Shortly before the election, the IBEW withdrew from the ballot leaving this now independent group to vie with a “no union” vote. They won overwhelmingly and declaring themselves the “Brotherhood of Consolidated Edison Employees” (BCEE) reformed along the original seven chartered lines. However, they also formed a “Council of Twenty-one” to which three members from each of the seven chartered groups were to participate. Shortly thereafter, Locals 1 and 2 decided to merge and, wishing to preserve their founding identities, called themselves Local 1-2.

Thus, in a relatively short time the employees broke away from the IBEW and became members of a new independent organization known as the Brotherhood of Consolidated Edison Employees, which they formed into six chartered groups with representation on an overseeing council. The first officers of this council were Joseph Fisher, Chairman; William Pachler, Secretary; and Clem Lewis, Treasurer. This council operated as a central body handling membership problems and negotiating contracts.

With subsequent company mergers, the union continued to respond by reorganizing to maximize its representation ability until ultimately Local 1-2 came to represent all the union employees at ConEd.

In the meantime, the CIO approached the Brotherhood in 1945 with an offer to combine forces with the UWOC and create a new, large, and powerful body in the CIO. In addition, a number of other independents with a relationship to the Brotherhood were expected to come along into this relationship.

At this point we shall leave the new flourishing Brotherhood to which we shall return later.

West Penn Power: ‘It Just Looked Easy’

In Pennsylvania things were far less complex. A number of employees of the West Penn Power Company felt the tug of the tide of unionism that was washing across the United States during this period and, by mid-1936, a group of employees consisting of Reginald Brown, Glenn (Whitey) Sevick, Merrill Vivian, Carl Oscar, Lawrence Ferguson, and George Bordell, began efforts in earnest to organize the Pennsylvania Power Station of the West Penn Power Company. Their job was so well done that the company needed no proof of interest and the local was established as the bargaining agent by early 1937. Immediately affiliating with the UWOC, chartered in as Local 102, they signed their first contract with the company on April 10 of that year, which became effective on the first of May. The first president of this new local was Reggie Brown, who as we know, went from there to an organizing job with the UWOC, and retired after years of active unionism as vice president of the National Utility Workers Union.

In Pennsylvania things were far less complex. A number of employees of the West Penn Power Company felt the tug of the tide of unionism that was washing across the United States during this period and, by mid-1936, a group of employees consisting of Reginald Brown, Glenn (Whitey) Sevick, Merrill Vivian, Carl Oscar, Lawrence Ferguson, and George Bordell, began efforts in earnest to organize the Pennsylvania Power Station of the West Penn Power Company. Their job was so well done that the company needed no proof of interest and the local was established as the bargaining agent by early 1937. Immediately affiliating with the UWOC, chartered in as Local 102, they signed their first contract with the company on April 10 of that year, which became effective on the first of May. The first president of this new local was Reggie Brown, who as we know, went from there to an organizing job with the UWOC, and retired after years of active unionism as vice president of the National Utility Workers Union.

In 1942, the local expanded to include the “Ridgeway” and Connellsville Power Stations. Finally, in 1944 with one giant step, the union took over the representation chores of all the physical employees of the West Penn Power Company.

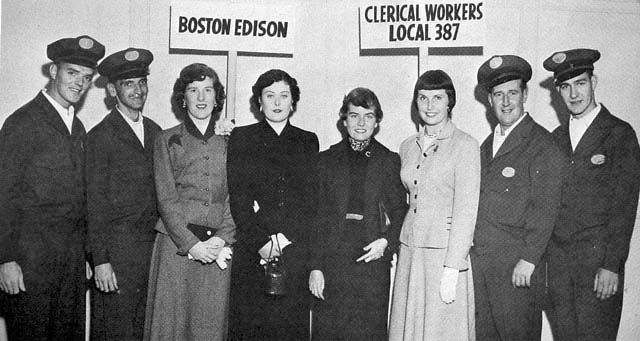

Boston Edison

Boston Edison: In the 1930’s and even into the 1940’s, Boston Edison Company was hostile to the growth of labor unions.

The company was powerful and influential, and had close ties to the New England banking and insurance establishments. Thus, they were tough enough to exercise this hostility; they did. They did their level best to keep unions off the property.

But as it always happens, along came someone, smarter and tougher. It was a new breed of unionist, this time armed with the rights given him by the National Recovery Act. The management, innovative fellows that they were, cast about looking for a way to prevent real unionism from taking hold, and they found a loophole in the Act that enabled them to establish – a bright new idea – a company union. They called it “The Boston Edison Employees Representation Plan.” Now where have we heard this before? But let’s give them a little credit, they called their committee, “Committee 86.” The number 86 meant 43 of them, 43 of us. Converted to the practical, it meant absolute veto power by the company. The employee representatives did the best they could but were confined to dealing with the mundane and unimportant. When Congress shot the Wagner Act arrow, it pierced, among others, “Committee 86.” Out hissed the air and in its place on July 27, 1937, the employees elected a true representative, “The United Brotherhood of Edison Workers.” The only thing they saved from the defunct “Committee 86” was the use of delegates to represent the members. The Brotherhood used 34 delegates, apportioned roughly to equal one delegate per 100 members.

The first contract they negotiated consisted of only nine pages and restricted arbitration to disputes involving discharges or wages.

For many reasons, the reign of this new union was not auspicious. Wages remained low and lagged glaringly behind defense plant pay. Benefit packages were not as full as expected and, in addition, were subject to company change or termination without protest. Union divisiveness resulting from tensions between the city and suburban workers began to grow. In general, the union was not delivering to the membership that which they had come to expect. Clearly, the union had its faults, not the least of which was lack of aggressiveness and experience, characteristics that could have been provided by a CIO affiliation. But the Brotherhood was not yet ready to affiliate.

They did toy briefly with an IBEW (AFL) affiliation, but the paucity of the AFL contracts compared with those of the Utility Workers prevented consummation.

Throughout this period, however, enthusiasm for UWUA affiliation was growing. In its first election attempt in 1943, the UWUA won 41 percent of the vote. They tried again in 1944 and increased their holding to 45 percent, and once again in 1948, scoring 47 percent for the UWUA. The 1948 vote was interesting in that many believe it would have been the winner had not the NLRB disqualified the Meter Readers (a very pro-UWUA group) by ruling them out of the production and maintenance bargaining unit.

Finally, in 1949 the Brotherhood fizzled out. After an eight-month delay, they had gotten the members a three percent pay hike, hardly what the membership was expecting. The Brotherhood offered a number of reasons for the delay and the disappointing end result, but the membership had had enough, and the excuses didn’t work, as we shall see.

The following year, the UWUA tried again. Harold Rigley, then UWUA organizer, with the help of William Davis, led the effort. This time it was different. On June 21, 1950, as the last few ballots remained to be counted, it was looking good. And it was. The final tally showed that 54 percent of the production and maintenance employees wanted the UWUA.

The production and maintenance workers held their first UWUA membership meeting on July 5, 1950; they had become Local 369. The Edison clerical forces quickly entered the UWUA, becoming Local 387, as did the professionals, becoming Local 386.

To quit at this point with a mere mention of the last two locals would be unconscionable. For regardless of the tripartite local structure now in place, it was in fact only through the united efforts of all the groups that unionism was achieved at Boston Edison. For example, it was mentioned above that the meter readers were excluded from the 1948 election. Had the NLRB decided differently, a victory would have been a near certainty. This strong pro-UWUA group was led by Val Murphy. He, along with Francis Kennedy, Leo Murray, Jim McNichols, Ken Pellegrini, Tom Sullivan, Tim Foley, Harry McDonald and Harland Parsons, never ceased the union drum beat until all that could, and all that would, became members of the UWUA. Whether it took one local, two locals, or three locals, the job would be done, and it was.

Southern California Gas

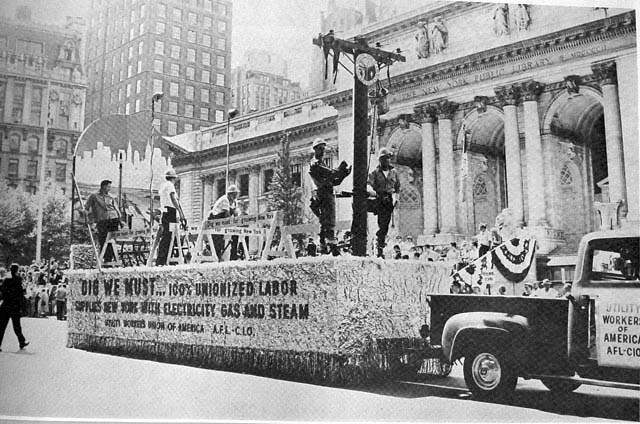

This time we will skip over the usual rise and fall of the company-inspired union, and go directly to the point where the employees elect a real representative. We will do this mainly to present an uncluttered look at one of the ways our large local unions gain in size and thus multiply their representational strength to better serve their membership.

Local 132 is just such an example, having been first organized by the UWOC in 1940 and having signed their first contract with Southern California Gas Company a year later. However, they were not long to remain the exclusive bargaining agent on the gas company properties. Throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s other UWUA chartered local unions were established. There was Local 114 in Van Nuys, Local 150 from Compton, Local 168 in Glendale, Local 170 in Bakersfield, Local 193 in Taft, Local 243 in San Bernardino, Local 279 in Avenal, and Local 290 at Visalia. A total of nine local unions, each representing a portion of the Southern California Gas work force.

Local 132 is just such an example, having been first organized by the UWOC in 1940 and having signed their first contract with Southern California Gas Company a year later. However, they were not long to remain the exclusive bargaining agent on the gas company properties. Throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s other UWUA chartered local unions were established. There was Local 114 in Van Nuys, Local 150 from Compton, Local 168 in Glendale, Local 170 in Bakersfield, Local 193 in Taft, Local 243 in San Bernardino, Local 279 in Avenal, and Local 290 at Visalia. A total of nine local unions, each representing a portion of the Southern California Gas work force.

In 1956, John Krevtz, president of Local 132 then representing the gas company employees in the Central Division of Los Angeles, broached the subject of merger with the other local unions. After long and thorough discussions, it became clear that better representation could be accomplished by consolidating their efforts and thus by 1962, all except Locals 243 and 170 became united under the Local 132 banner. With this united strength they could afford full-time representation, and they elected Harold Trusler as president and Ed Hall as secretary-treasurer to serve as full-time officers. In 1973, San Bernardino Local 243 merged with Local 132, leaving only one of the original nine locals (Local 170) yet separate. Since that time, Local 522 representing sales and marketing employees, and Local 483 representing transmission employees, have been chartered by UWUA as affiliates. Currently, the approximately 3,500 unionized employees of Southern California Gas are in the main members of Local 132, although a portion continue as members of Local 170, Local 522, or Local 483. In any event, the locals combine their efforts and negotiate jointly with the company, arriving at settlements voted upon by the full union workforce and applicable to all.

Dayton Power and Light: ‘All or Nothing at All’

It gets tiresome but it seems we must begin each local history with a company version of unionism. Dayton Power and Light was no exception. A few sheets of plywood, a bit of wire and a few nails and next thing you knew, the company had erected a brand new union hall to take your problems to. Unfortunately, it was only three inches deep. A trip through the door with an overtime complaint, a low pay gripe, or a claim of favoritism left one approximately where one began – “outside.”

It didn’t take long to tire of this nonsense and the employees began to flirt with the IBEW. They went so far as to schedule an election, but the IBEW pulled out under suspicious circumstances on the day of the vote. Undaunted, the employees insisted on organizing and they brought in the “Utility Workers Organizing Committee.” It wasn’t but a short while later that they were set to petition for another election. After thinking a while, the hotshots in management came up with their next brilliant scheme to outwit and finesse the union. They insisted that the clerical and sales employees be included in the representational election; the thought being to water down the vote, and sink the unionizing effort.

The election was held, and by a close vote the red-faced and egg-encrusted management discovered that the union won them all. With a tip of the hat for the unintentional assist, the union now spoke not only for the production and maintenance employees but for the clerical and sales forces as well. On June 17, 1941, Local 175 became a UWOC chartered union.

Although it’s not recorded, it’s a safe bet that the company, after booting the election, pouted through their first negotiations with the union. Pouted to the point that seven issues were left unresolved. Being the war years, the government had established the “War Labor Board” to resolve such disputes. Petitioning the Board, the union obtained their demands in five of the seven issues. Namely, wages, back pay, overtime distribution, vacation entitlements, and sick time.

With this, Local 175 became the recognized union at Dayton Power and Light, and possessor of the first signed contract. It was some time after the signing of the contract that both parties agreed that the sales representatives were difficult to represent, and this group was returned to their original unorganized status. Since then, Local 175 has represented both clerical workers and the production and maintenance workers at Dayton Power and Light.

Detroit Edison: ‘They Club Seals Don’t They?’

If anyone thought that the Detroit Edison Company would try to start a company union and call it an “association” or a “council,” as others had, they would have been wrong. Such pedestrian tactics were hardly Detroit Edison’s style. The company would never sink to a level so mundane. Oh, they started a company union all right, but they called theirs a “club.” The “Customers Service Division Club” (CSD) to be exact. Now what could be more classy and comforting than belonging to the “club”? One suspects the CSD Club could have just as easily been called the “LSD Club.” For the effect was to keep the “clubbies” tranquil and happily believing in a world that didn’t exist.

When this didn’t work they switched to the more conventional approach. You guessed it: The Detroit Edison Employees Association (DEEA). They went so far as to draw up a set of bylaws and try to get board certification. Surprisingly, in 1945 they actually got NLRB certification as representatives for employees in the Customer Accounts Department.

But this lasted only a short time; in fact, it wasn’t long before the whole mess, the Club, the Association, and another try called the “Substation Workers Council” went down the drain.

Real unionists were not asleep during this period, however, and a group of employees working with the Utility Workers Organizing Council put together a local union chartered and affiliated by and with the UWOC in 1943. The union was Local 223, then in its infancy and representing a few power plants and departments with working negotiated contracts. They did not come by these contracts easily. In several instances, they had to carry the battle to the War Labor Board to win their terms. In any case, these contracts reflected for the first time guarantees of better working conditions. Clauses were added that provided for time and one-half on the sixth day, and double time on the seventh day. Minimum pay callout provisions were inaugurated, as was premium pay rights after 12-hour stints of duty. Issues of vacations and sick pay were addressed and adjudicated, as were the beginnings of other provisions that now form some of the basics of the current agreement.

These contracts and the representation they provided began to convince other groups of workers in the company that Local 223 was the way to go.

This acquisition of group after group of workers is an interesting facet of the Local 223 operation. Although it is not unusual for a local union to pick up members in a piece-meal fashion with independent certifications, this local’s history shows this technique clearly. It began with the electrical system substation’s certification in February of 1943, followed almost immediately by certifying the Conners Creek Power Plant and the Trenton Channel Plant. Underground lines joined the union in June of 1943 and within days the Construction groups, both Field and Shop, entered the fold. The certification of Building and Properties, Marysville Power Plant, along with the Food Service people at this location, the Delray Power Plant and Motor Transportation completed the 1943 organizing efforts.

The Detroit-area Meter Readers joined up in 1944, as did the Central Heating group in 1946. Also in 1946, the Food Service groups at both Conners Creek and Delray Power Plant came on board, with the Food Service employees at the Trenton Channel Plant several years later in 1952. In 1953, it was the Stores Department’s turn. In 1957, the Food Service employees at both the St. Clair and River Rouge Power Plants preceded other employees in those locations into the union. It wasn’t until 1960 that the entire St. Clair Power Plant and the River Rouge Plant workforces became organized. Employees at the Pennsalt Power Plant became members in 1964.

A few years went by and then Meter Service, the Harbor Beach Power Plant and the Greenwood Plant all joined in 1968. In 1969, the Maintenance Amendment was signed and, in 1971, Monroe Power Plant entered the union, with Food Services following in 1976.

Employees at Enrico Fermi I and II, as well as those in General Offices and Services Building Restaurant Division, joined up in 1972. The Meter Readers in Oakland County affiliated in 1979, and in 1982, completing the list, the Food Service workers at Fermi I and II became members of Local 223.

In all, 23 separately certified bargaining units all doing business through the central offices of Local 223.

To put together a lengthy organizing history such as this requires a continuing display of strong representation, good contracts, and able leadership. Apparently Local 223 has all three.

Standing But Still Shaky

As you can see from the foregoing samples, our local unions did not follow a specific and duplicating pattern of evolvement. Each was born and grew in a different and interesting way. Left to themselves, they may have floundered and fallen. It was the intention of the UWOC leaders to prevent this from happening.

Non-affiliate organizations were snipping and biting, trying to tear away a piece at a time from the UWOC fabric. Even some of the local unions themselves, concerned as they were with their immediate and separate problems, did not perceive the benefits that could be reaped from a coalition of forces pointed at the same goals. Suffice to say, there was some diversity of purpose and a real possibility that this fragile network would collapse.

Now was the time to cement the gains, to raise a flag for all to rally about, to coalesce into a whole, and set about laying the foundations upon which would be erected a free-standing and long-enduring organization espousing the principles of unionism and having the strength to reach its goals.

The Second Big Step

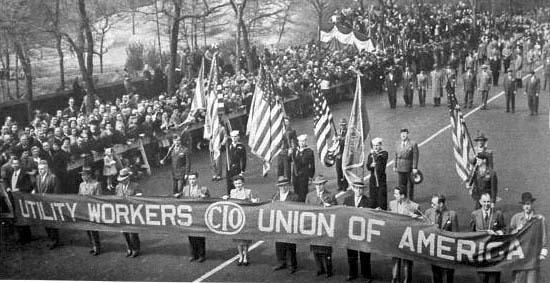

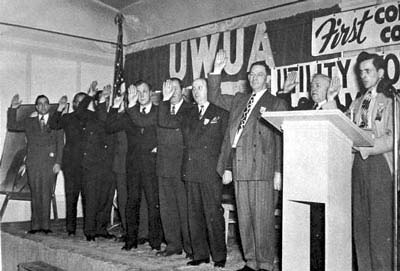

This was the next step and this takes us to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (the birthplace of the CIO). The place is the ballroom of the Roosevelt Hotel. The time is the morning of October 31, 1942.

Shortly before noon, upwards of 50 delegates representing approximately 180 local unions, gather to hear the gavel bang to order the “First Constitutional Convention of the Utility Workers Organizing Committee.” The purpose? Well let’s let the record speak for itself. Following the invocation and addresses by temporary chairman, Regional Director Anthony Federoff, and Allen Haywood, national director of the CIO, Regional Director Harold Straub rises to deliver the Officers’ report. He says as a preamble:

I have always had the opinion that our people wanted their own National Union, affiliated only with the C.I.O. If I am wrong, now is the time to say so.

The establishment of the Utility Workers Committee in 1938 was the first step toward the setting up of a National Union. This Constitutional Conference is the second step in that direction and should result in the complete solidification of our forces to the extent that we will leave the City of Pittsburgh determined to work together, shoulder to shoulder, for the common good of all utility workers of the nation and toward the setting up of our own National Utility Workers Union.

As was well-stated, this was the major aim of the delegates who attended this First Convention. An aim that was true as subsequent events have proven.

For those who are interested, let us list the local unions then in the UWOC along with the companies under contract as they appeared in official minutes, and follow this with a list of the delegates that were present.

UWUA Locals and Contracts, October 1942

Locals and Contracts – Utility

Local 102, Springdale, PA, with West Penn Power Co.

Local 108, Anderson, IN, with Municipal Light Plant

Local 116, Newcomerstown, OH, with Ohio Power Co. Serv. Div.

Local 118, Youngstown, OH, with Ohio Edison Co.

Local 121, Chattanooga, TN, with City Water Co. of Chattanooga

Local 122, Morgantown, WV, with Morgantown Water Co.

Local 127, Casper, WY, with Mountain State Power Co., Wyo. Div.

Local 138, Philo, OH, with Ohio Power Co.

Local 146, Danville, IL, with Interstate Water Co.

Local 155, Ellwood City, PA, with Ellwood Consolidated Water

Local 156, New Kensington, PA, with West Penn Power Co.

Local 160, Stockton, CA, with California Water Serv. Co. (3 contracts)

Local 160-C, San Mateo, CA, with California Water Serv. Co. (2 contracts)

Local 161, Kittanning, PA, with Kittanning Telephone Co.

Local 162, Fairmont, WV, with Monongahela West Penn Public Serv. Co.

Local 164, Greensburg, PA, with Westmoreland Water Co.

Local 171, New Castle, PA, with City of New Castle Water Co.

Local 174, Pittsburgh, PA, with So. Pittsburgh Water Co.

Local 176, Huntington, WV, with Huntington Water Corp.

Local 180, Altoona, PA, with Pennsylvania Edison Co.

Local 186, New York, NY, with N.Y. Water Serv. Corp. (2 contracts)

Local 191, E. Pittsburgh, PA, with Penn Water Co.

Local 198, Elizabeth, PA, with Monongahela Valley Water Co.

Local 205, Bakersfield, CA, with California Water Serv. Co.

Local 220, New Kensington, PA, with Kensington Water Co.

Local 221, Vandergrift, PA, with Vandergrift Water Co.

Local 230, Butler, PA, with Butler Water Co.

Local 249, Paterson, NJ, with Public Serv. Elec. & Gas Co.

Locals and Contracts – Railroad

Local 166, Brookville, PA, with Pittsburgh & Shawnut RR Co.

Local 173, St. Marys, PA, with Pitt. Shawnut & Northern RR

Local 188-I, New York, NY, with Roma Bros. (Penn RR Station)

Local 213, Jersey City, NJ, with Hudson & Manhattan RR Co.

Local 1420, Los Angeles, CA, with Pacific Elec. Railway Co.

Local 235, Knoxville, TN, with Smoky Mountain Railroad

Systems with Utility Workers Organizing Committees

ORGANIZATION IN MORE THAN ONE DIVISION

System: American Water Works & Electric Company

Local 102 – Springdale, PA – West Penn Power Co. (Div.)

Local 156 – New Kensington, PA – West Penn Power Co. (Div.)

Local 121 – Chattanooga, TN – City Water Co. of Chattanooga

Local 122 – Morgantown, WV – Morgantown Water Co.

Local 164 – Greensburg, PA – Westmoreland Water Co.

Local 174 – Pittsburgh, PA – So. Pittsburgh Water Co.

Local 171 – New Castle, PA – City of New Castle Water Co.

Local 176 – Huntington, WV – Huntington Water Works

Local 178 – Connellsville, PA – Trotter Water Co., Connellsville Water Co.

Local 191 – E. Pittsburgh, PA – Pennsylvania Water Co.

Local 211 – Verona, PA – Suburban Water Co.

Local 220 – Kensington, PA – Kensington Water Co.

Local 221 – Vandergrift, PA – Vandergrift Water Co.

Local 230 – Butler, PA – Butler Water Co.

Local 162 – Fairmont, WV – Monongahela West Penn Public Serv. Co.

Local 179 – Fairmont, WV – Monongahela West Penn Public Serv. Co.

Local 198 – Elizabeth, PA – Monongahela Valley Water Co.

System: American Gas & Electric Corporation

Local 116 – Newcomerstown, OH – Ohio Power Co. (Div.)

Local 138 – Philo, OH – Ohio Power Co. (Div.)

Local 172 – Canton, OH – Ohio Power Co. (Div. 1)

Local 187 – Elida, OH – Ohio Power Co. (Canton General Div.)

Local 159 – Power, WV – Beech Bottom Power Co.

Local 180 – Altoona, PA – Penn Edison Co.

System: Standard Power & Light Corporation

Local 110 – McKeesport, PA – Duquesne Light Co. (Div.)

Local 117 – Springdale, PA – Duquense Light Co. (Div.)

Local 190 – Pittsburgh, PA – Duquense Light Co. (4 Div.)

Local 127 – Casper, WY – Mountain States Power & Light (Div.)

Local 197 – Marshfield, OR – Mountain States Power & Light (Div.)

System: Commonwealth & Southern Corporation

Local 118 – Youngstown, OH – Ohio Edison Co. (Div.)

Local 126 – Akron, OH – Ohio Edison Co. (Div.)

Local 181 – Toronto, OH – Ohio Edison Co. (Youngstown Div.)

Local 113 – Lansford, PA – Penn Power & Light (Div.)

Local 140 – Sharon, PA – Penn Power & Light (Div.)

Local 101 – Jackson, MI – Consumers Power Co. (all Consumers Power Locals are divisions in cities’ names, except where otherwise specified)

Local 103 – Muskegon, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 104 – Saginaw, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 105 – Pontiac, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 106 – Battle Creek, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 107 – Grand Rapids, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 119 – Flint, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 123 – Lansing, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 124 – Manistee, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 129 – Alma, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 144 – Bay City, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 150 – Kalamazoo, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 154 – Cadillac, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 253 – Owosso, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 254 – Mt. Clemens, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 257 – Hastings, MI – Consumers Power Co. (Hastings & Charlotte Divs.)

Local 258 – Adrian, MI – Consumers Power Co.

Local 261 – Six Lakes, MI – Consumers Power Co.

System: Public Service Company of New Jersey

Local 167 – Jersey City, NJ – Harrison Gas Plant

Local 249 – Paterson, NJ – Paterson Gas Plant

System: California Water Service Company

Local 160 – Stockton, CA – San Joaquin County

Local 160-B – Concord, CA – Concord Plant

Local 160-C – San Mateo, CA – San Mateo County

System: East Ohio Gas Company

Local 148 – Akron, OH

Local 229 – Canton, OH

System: Southern California Gas Company

Local 132 – Los Angeles, CA – Central Div.

Local 114 – Van Nuys, CA – Van Nuys Div.

Local 151 – Los Angeles, CA – Central Div.

Local 152 – Compton, CA – Southern Div.

Local 168 – Glendale, CA – Northern Div.

Local 170 – Oildale, CA – Oildale Area

Local 193 – Taft, CA – Taft area of Kern Div.

Local 243 – Riverside, CA – Eastern Div.

Local 250 – Los Angeles, CA – Santa Monica Div.

System: Pacific Gas & Electric Company

Local 133 – San Francisco, CA – (Divisions of this company are in the cities named unless otherwise specified)

Local 134 – Oakland, CA

Local 135 – San Rafael, CA

Local 136 – San Jose, CA

Local 137 – Redwood City, CA

Local 139 – Stockton, CA

Local 169 – Oakland, CA – Contra Costa County

Local 225 – Sacramento, CA

Local 233 – Bakersfield, CA

Local 236 – San Rafael, CA

Local 241 – Santa Rosa, CA

Local 246 – Long Beach, CA

Railroad Systems Where UWOC Has an Organization

Alton Railroad Co.

Atchinson Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad Co.

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co.

Boston & Maine Railroad Co.

Brookville Locomotive Co.

Buffalo Creek Railroad

Central Railroad of New Jersey

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co.

Chicago Great Western Railroad Co.

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad Co.

Chicago & Northwestern Railroad Co.

Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway Co.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Co.

Detroit Shore Line Railroad Co.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad Co.

Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railroad Co.

Erie Railroad Co.

Erie Railroad Terminal

Grand Trunk Railroad Co.

Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Co.

Illinois Central Railroad Co.

Lake Erie & Eastern Railroad Co.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co.

Michigan Central Railroad Co.

New York Central Railroad

New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Co.

Pacific Electric Railway Co.

Pennsylvania Railroad Co.

Pere Marquette Railroad Co.

Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad

Pittsburgh, Shawnut Railroad

Pittsburgh, Shawnut & Northern Railroad Co.

Pullman Co.

Reading Railroad Co.

Rutland Railroad Co.

Smoky Mountain Railroad Co.

Southern Railway

Texas & Pacific Railroad Co.

Union Depot Co. – Cleveland Union Terminals

Wabash Railroad Co.

Delegates to the First UWOC Constitutional Convention

Dan R. Kelly

Joseph Logue

James J. Molinet

Martin O’Dell

J. L. Orr

John S. Phillips

Luther Richardson

Lester S. Shaull

D. H. Stephens

Milton Stone

Victor Tunberg

Charles H. Willoughby

Alfred C. Bender

Reginald Brown

George Carson

Thomas Clark

Charles P. Cunningham

Joseph Demay

Edwin Fawcett

Edward Fooks

Wm. H. Hartmann

J. A. Hanes

Richard J. Hoolihan

Alvin C. White

Edwin B. White

L. J. Kane

Francis McMahon

Joseph J. Musingo

Emil Olscher

Earl Chester Randles

William E. Powers

Henry Renzi

Edward T. Shedlock

E. S. Stockwell

Eugene Teeter

Charles Wienand

Arthur Bibbee

Andrew R. Boyd

Wilbert Butcher

Herman Chadwick

Charles M. Coyle

James L. Daugherty

Raymond A. Dodge

Woodrow Fisher

Fred Frederich

Lemoine Harvey

Glen B. Henney

J. L. Johnson

Dale C. Whitney

John T. Wood

These delegates hunkered down for two days in morning, afternoon, and evening sessions, and hammered out the rules and selected leaders that would assure an orderly transition to the final step of organization. It should be understood that the delegates knew that they were not fashioning an ultimate entity, but were instead tightening the stays and fine-tuning the rigging for the final leg of a journey, that had as its terminus, the long awaited result, a fully-operational, free standing, chartered National Union, having a stature and strength equal to the task of bringing solid representation to its membership.

Throughout the proceeding there were arguments and debates, but differences were resolved with surprisingly little rancor.

By the sixth session of the convention, called to order at 8:30 on a Sunday evening, the body was ready for the last order of business, the selection of the regional members of the Executive Committee. Within an hour, they nominated and elected the following individuals:

Region I – Victor Tunberg

Region II – Reginald Brown

Region III – Raymond Dodge

Region IV – Herman Chadwick

Region V – James Daugherty

Region I (railroad) – Richard Houlihan

Region II (railroad) – E. S. Stockwell

With the completion of this final piece of business, the first and last Constitutional Convention of the “Utility Workers Organizing Committee” was adjourned. The next time they were to meet, in April 1946, they would be known as the Utility Workers Union of America, CIO.

Things Keep Happening

But, much took place between these meetings. In the intervening period, the UWOC saw an opportunity to greatly enhance the strength of this about to be created national union by the addition of a large block of members from the new, vibrant, and progressive Brotherhood of Consolidated Edison Employees, and to this end, they entered into serious discussions with the leaders of this group. Needless to say, much was to be gained in strength and representational ability by both the Brotherhood and the UWOC.

Ultimately, they fashioned an alliance with a strength greater than the sum of its parts; a new national organization composed of all the local unions affiliated with the Utility Workers Organizing Committee and the Brotherhood of Consolidated Edison Employees. This they christened the “Utility Workers Union of America, CIO” and chartered this organization on August 1, 1945. That’s the date the Utility Workers Union of America became a national organization.

To preserve and cement this new organization together until a constitutional convention could be held, Philip Murray, president of the CIO, met with representatives of both the Utility Workers Organizing Committee and the Consolidated Edison Employees and designated temporary officers to serve in the interim period. He selected Joseph Fisher from the Brotherhood to serve as temporary president; William Pachler, also from the Brotherhood, as temporary secretary. From the UWOC, he picked Harold Straub and William Munger to serve as vice presidents until a convention could be held.

April is not a month in which one packs a lunch and looks forward to a day at the beach. Certainly, not a northeastern beach touched by the Atlantic Ocean. A stroll on the boardwalk in Atlantic City at this time of year is an invigorating experience. This was especially true in 1946, with no casinos to duck into if one became chilled. Yet, in spite of this, there were a goodly number of people taking the air on the sixth and seventh days of April.

If the curious were puzzled by this unseasonable influx of pedestrian traffic, they need have looked no further than the events listing in the lobby of the Breakers Hotel to discover the reason. The first Constitutional Convention of the “Utility Workers Union of America, CIO” was in session, and a flood of delegates were in town to do the business of this newly created National Union.

Setting Up Shop

So here they were and ready to go! Here were the people who were about to affect the lives of many who would succeed them. There was a hint of promise and anticipation, an excitement that each of them felt, for they were gathered together to launch a new national union. A union not only new in origin but new in concept. A Utility Workers Union. A union designed to address the concerns of a group of workers who until now had no national focus. There were organized garment workers, steel workers, rubber workers, and batters and dyers and packers, as well as numerous others. But until now no one spoke for utility workers. If all went well, that would soon be changed.

The convention opened at 10:30 a.m. on April 6 and almost at the beginning Joseph Fisher, president pro-tem, deviated from the printed agenda to introduce Allan Haywood, organizing director and vice president of the CIO.

It was rightfully done, for here was a man who had so much to do with bringing about the creation of the UWUA. Haywood conceptualized and brought into being the “Utility Workers Organizing Committee,” the seed of the UWUA. He chaired the committee, selected the staff, and directed the operation. And he was here today to see the concept into a reality.

What better way to open the convention:

Brother Haywood: President Fisher, Associate Officers, Reverend Father Carey and members of my union, the UTILITY WORKERS UNION OF AMERICA.

This is a red letter day, this day, April 6, 1946. In years to come, everyone here will refer back in some manner to this day at this Convention. You are making history.

To Father Carey, it was a day of joy. I want to assure him that I share with him that joy. I have looked forward to the day when the utility workers of our nation would form their own national union. Here is the day, a dream come true. The eyes of the country are upon you.

I talked with your president yesterday – and my president – a man who can be easily – and I say this in all humility and modesty – the greatest labor statesman that we have produced in this great country of ours. He is in Pittsburgh, dealing with the affairs of another great union of human beings, United Steelworkers of America. He asked me to extend to you his best wishes for a successful and a united Convention. He told me to tell you when you leave this Convention, the CIO will join with Brother Fisher and Brother Straub and Brother Pachler, and the other officers, in rolling your Union forward. He asked me to wish you God speed and he sent this message:

William J. Pachler, Secretary-Treasurer

Utility Workers Union of America

1133 Broadway, New York

Please convey to delegates attending First Constitutional Convention of Utility Workers Union of America my sincere regrets that I cannot be present personally and my best wishes for a most successful Convention. The launching of your Union is a great step forward in the history of American Labor and the CIO. It brings new hope to utility workers throughout the country promising many improvements in wages and working conditions and adding a new phalanx to the progressive labor movement. The unity and strength of your new organization will add greatly in organizing the unorganized and you can rest assured at all times of the wholehearted and energetic support of the whole CIO in your constructive endeavors.PHILIP MURRAY

The flavor of the convention was probably captured in this portion of Haywood’s remarks and the message sent by Philip Murray. With these thoughts on their minds, the delegates commenced the business of the convention.

Committees Make It Work

Conventions run as smoothly as they will only because of the committee structure. Here are the delegates who did the important committee work at the UWUA first convention:

Convention Committee

Clarence Sogard, Chairman, Region V

Andrew McMahon, Region I

Robert Gordon, Region II

Ross Stephens, Region III

Norman Smith, Region I

William Good, Region IV

Nominations

A. B. Ferguson, Chairman, Region III

Mort Witzman, Region I

George Blair, Region II

Charles Palmer, Region I

R. WeakleY, Region V

Emerson T. Campbell, Region IV

Constitution

Perry C. Altman, Chairman, Region II

John Wynne, Region I

Edmond Ward, Region III

Michael Sampson, Region I

L. R. Watterinan, Region V

Henry Kerouac, Region IV

Credentials

Martin O’Dell, Chairman, Region IV

Kenneth Moser, Region II

Irvin Koons, Region III

Edward Marsine, Region I

Carl Stahlecker, Region V

Robert Glover, Region I

Resolutions

Stephen Gallagher, Chairman, Region I

Arthur Haggerty, Region I

John S. Phillips, Region II

John McCartney, Region III

Orno L. Knowles, Region IV

Lynn Hames, Region V

Arrangements

Arthur Hawks, Chairman, Region I

George Carson, Region II

R. J. Hartley, Region III

Francis Thompson, Region IV

Joseph Dawson, Region I

Committees do much of the hard work of conventions, but no committee worked harder and longer than did the Constitution Committee at this convention. For you see, there were two major pieces of business to be conducted these two days.

The first was the election of the national officers who were to see to it that the first steps of this youthful organization were set upon a productive path, and who would then be further obligated to make certain that each following step was more firmly planted.

The second and equally important task was the construction of a constitution – that basic law of the organization that encapsulates the will of the body and declares its purpose, and that establishes the rules that the governed chose to be governed by. It is not a job to be taken lightly. Properly done, it will form a sound basis upon which will be predicated actions occurring far in the future.

Although we can say in retrospect that the job was accomplished with only moderate debate and discussion, this was hardly the end the delegates perceived this Saturday morning when the chairman of the Constitution Committee reported out the result of the committee deliberations on Article III of the shaping constitution.

Committee Chairman Perry Altman: By a vote of five to one, with one region dissenting, the Committee recommends adoption.

Just an inkling of things to come. But to the perceptive delegate, it meant that the convention would soon hit a snag. Just what was contained in Article III that would cause a disruption?

Before we examine the contents of Article III, we should reflect again as we did earlier, upon early days of unionism and the world into which this movement was born.

As we go about our practice of unionism today, handling grievances, arbitrating disputes, negotiating contracts, we are drawn to the conclusion that unionism is best described as the practice of representation based on a system of legal and quasi-legal restrictions and grants that enables us to render a measure of industrial justice. But unionism was, and still is, much more than that.

The deeper meaning of the labor movement was more easily seen at the time of the first UWUA convention. It would be safe to presume that every delegate in attendance had a clearer understanding of this deeper involvement than we do today. After all, they were on the scene when this explosive force erupted. They were witness to the early effects of the impact. They knew of and were not surprised by the bloody battles that swirled around the scenes of its implementation, for they knew the stakes were extremely high. At that first convention, everyone intellectually or intuitively knew they were part of a movement that would completely reshape the American society. We know now that their assessment was correct.

Of all the forces of change that have impacted on the American society, few would deny that the effect of the labor movement was one of the most profound. It completely reordered society’s priorities. It created an unbelievable re-distribution of wealth. It created, single-handedly, the middle class in America. In fact, it reshaped the very ethos of the society.

In the process of emancipating the working man and woman, the labor movement changed the society. From this viewpoint it was a societal movement, and was perceived correctly as such by many outside the house of labor. It attracted the sane and the senseless; the conservatives and the crazies. All sorts of people who saw this as an opportunity to shape these changing standards to a form more suited to their tastes. It comes as no surprise that the labor unions themselves attracted such people. After all, the unions, whether they wanted to be or not, were at the forefront of the change, they were the shapers of this society’s future. That there were socialists, communists, fascists and even Nazis in labor’s ranks or trying to get into these ranks could hardly be questioned. Every major union was faced with the problem. The question was what to do about it. Unions were in favor of change, in this there can be no doubt, but they were against any change that was anti-democratic. Yet, the world was not composed only of bomb-throwers and non-bomb-throwers; there were many gradations and subtle variations; there were people whose attitudes and outlooks were hard to characterize and impossible to label. Now the delegates were to be faced with the question, “Where does one draw the line?” Article III drew the line:

Any member accepting membership in the Communist, Fascist, Nazi, or any other subversive political party or organization shall be expelled from the Utility Workers Union of America, and is permanently debarred from holding office in the Utility Workers Union of America, and no members of any Communist, Fascist, Nazi or any other subversive political party or organization shall be permitted to have membership in our Union, unless they withdraw from such Communist, Fascist, Nazi or any other subversive political party or organization and forfeit their membership therein. Representatives, either verbal or written, of any employer or employer’s agent or non-member shall not be considered by the Union in determining whether or not anyone charged with being a member of the aforementioned parties or organizations actually holds such membership.

Hardly Ambiguous! Hardly Unclear!

It provoked a motion to delete and the debate was on. It seemed that almost everyone had something to say. The minutes indicate that the debate ran on for many hours. As could be expected, the delegates grappled with the gray areas. No one stood up and avowed membership in the named political parties nor were the beliefs or tenets of such parties espoused. What was debated was the wisdom of exclusion, the ethical right to exclude, and finally, the effect upon the organization caused by the adoption of either position.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to sum up the statements made on both sides of the issue into an expression of general positions. Maybe some random bits of transcript that give opposing delegates’ views will give us a bit of the flavor. (Note: They are not in context or order.)

Delegate: I would like to point out that I have fought for organization in this industry and that I have fought hard for it. I have stood in front of the plants, and wherever I have gone, I have been called a Communist, although I am not a Communist. It has been used against me. It will be used even as I rise here to speak as a delegate. The members who I represent and who I speak for – and rank and file – they know where I stand. I have always made myself clear to these people on these issues.

I am for an organization of everybody on the properties, regardless of the color of his skin, his religion, his nationality, as long as he thinks with me that the working class are entitled to a decent living.

Delegate: Brother Chairman and Fellow Delegates; I rise to put myself on record very definitely against the motion now proposed, to delete this clause from the Constitution. I would like to go a little bit further, because I am afraid the idea might be being created here this afternoon, that some of the things that have been said by the C.I.O. in the past are true. I say that insofar as the Utility Workers Union of America as it stands today, is concerned, and as far as the old Utility Workers Organizing Committee of the C.I.O. is concerned, they are not and they were not Communist. But, it wasn’t because some people didn’t try to make them that way.

People that are talking about the effect that such a clause will have in our Constitution, let me speak to them from experience. I have tried to organize utility workers practically all over the United States of America, and I can tell you of some sad experiences we had. We can beat the I.B.E.W. We can beat District 50 of the United Mine Workers of America. We can beat independent unions. But we couldn’t beat the stigma of Communism that was hung on us by these people, because we didn’t have this kind of a clause in the Constitution of the Utility Workers Organizing Committee. And we didn’t have it, because the very people who are fighting against putting it in there today, are the very ones who fought against it in the past.

I think it is time for everybody in this country, and particularly utility workers that are unorganized, to realize that this is an organization that is made up of, by, and for utility workers. It owes no allegiance or obligation to any political party whatsoever, particularly not the Communist party.

I, in all sincerity, urge you to vote down this motion.

Delegate: When I asked for the floor to speak in favor of this motion, a member seated in front of me called me a Communist immediately. It is very hard to tell who the Communists are. I don’t care who they are, because in this Union, I am primarily interested in fighting the Company. I think the vehemence and the attacks on the officers and the membership should be put on the backs of the light and power industry. I am not a Communist. I am an American.

Delegate: The previous speaker would lead us to believe that they needed an awful lot of time to discuss this problem. It would take me about two seconds to give my idea of what I think about it. I think any level-headed American in this room today would just take about the same amount of time – two seconds. When it comes to kicking Communists and Fascists and Nazis and all the rest of them out of this organization, and keeping them out, that takes about two seconds.

Delegate: I want to just mention to you that I agree with the first speaker one hundred percent. The C.I.O. and the Utility Workers is not – definitely not – a Communist organization. It never will be probably. It likewise will never be a Socialist or Fascist or anything else. It is an organization of workers binding themselves together for their own protection. Once you start excluding workers, I don’t care what they are, race, creed, color or because of a religious belief, or a political belief, you have already laid the groundwork to split your organization.

Delegate: I had the pleasure of serving on the Constitution Committee. I’d like to point out to this delegation that in considering this particular section, we on the Constitutional Committee spent close to six hours on this Section 5 of Article III. We knew when we went into session that we were there to build a strong Utility Union. That is the job we attempted to do. Now in building that strong Union, we know that it is necessary to maintain the strength of this country, the government that governs us at the present time. If there is any element in the country, regardless of what they call themselves, who is attempting to tear down the government of the United States, they are in effect tearing down the life-blood of this Union, because without the right from the Government, we would not be sitting at this Convention today.

We have seen too well in the last eight years, where we have had Communism, Fascism and Nazism, where a Union couldn’t function democratically, the way we are doing it here today, and if for no other reason than to perpetrate a Utility Workers Union for the rest of our lives, we should vote against this motion to delete from the Constitution.

The words threatened to flow endlessly. The delegates finally imposed a time limit. The debate was ended and a vote taken. By a near overwhelming margin they decided that “the clause stays!”

Today we carry with us evidence of this debate. Some of you may have noticed, and maybe considered archaic, item number one on the back of your union card. If you are curious and your card is in your wallet or purse (and it certainly should be) take it out and give a look.

There were five other clauses in the Constitution that were considered controversial, but they were resolved with relative dispatch.

The other major business before the convention was the election of officers who would occupy for the first time, executive positions in this new National Union.

The nominating committee offered the following:

Committee Chairman Ferguson: The Nominating Committee wishes to make the following report:

Nomination for President – Joseph A. Fisher

Nomination for Vice President and Director of Organization – Harold J. Straub

Nomination for Vice President – William Munger

Nomination for Secretary-Treasurer – William J. Pachler

For Members of the Executive Board:

Region I – Patrick McGrath

Region II – Reginald Brown

Region III – Irvin Koons

Region IV – Garland Sanders

Region V – James Dougherty

The three Executive Board members to be elected at large:

Martin O’Dell from Detroit, Michigan

Edward Shedlock from Youngstown, Ohio

Edward Marsine from Brooklyn, New York

I move that the Report of the Nominating Committee be accepted. This motion was seconded.

The motion to adopt was unanimous. There were no further nominations, and the above named officers became the first of a line of leaders of the Utility Workers Union that extends to this day and we suspect, will extend far beyond.

Conventions End But History Doesn’t