The U.S. job market has been on an upswing for more than two years with unemployment in early 2023 at its lowest level in more than half a century. Most industries are now above or close to their pre-pandemic levels of employment. At the same time, workers are engaging in a wave of unionizing. According to economists, the abundance of alternative employment is encouraging workers toward greater activism.

“I believe we are on the cusp of the next great wave of worker organizing,” Susan Schurman, a labor professor at Rutgers University, told Bloomberg Law. “Overall, I think there’s a generation of workers that are not going to be happy with being treated like a factor of production with no rights at all at work.”

The forecast may take a turn, however. Inflation continues to rise, putting downward pressure on wage gains and purchasing power. This is a unique – but perhaps fleeting – moment in the economy. It’s also a moment when unions can still stand to make significant gains.

New unionization drives in 2022

In 2022, workers voted to unionize at some high-profile companies with no history of labor organizing like Google, Trader Joe’s, Chipotle, Apple, and Starbucks. Other big union victories last year were at an Amazon warehouse in New York (which the company has challenged) as well as among graduate students at MIT, healthcare workers at Kaiser Permanente, and auto workers at a GM-owned electric vehicle battery plant.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) reported 1,928 union elections in 2022, a jump of over 50% from the prior year and the highest number of elections since 2015. Unions prevailed in 72% of elections last year.

“Workers have a lot of bargaining power, and that is fueling a resurgence in the labor movement,” said Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, told the Washington Post. “Unions are trying to make real lasting inroads during this period.”

The tight job market underpins labor’s relatively strong position. Meanwhile, popular support for organized labor reached its highest in 53 years in 2022 at 71%, according to a Gallup poll.

What is driving labor’s strength?

Several forces have converged to give workers more power than in the recent past. The exodus from the labor force called the “great resignation” during the COVID pandemic tightened the job market, and the rate of people quitting has remained relatively high.

“There’s a combination of things that have contributed to this organizing wave that we’re seeing, and the pandemic and post-pandemic economy have been a large part of that,” John Logan, a labor studies professor at San Francisco State University told the Washington Post. “It has opened up an opportunity for unions that didn’t exist before the pandemic.”

Some Americans continue to rethink their employment after the pandemic subjected many in public-facing jobs to safety hazards and increased stress.

“The pandemic was the wakeup call or the catalyst that has prompted two perspectives: ‘Is there another way to work and live?’ and the relationship between employers with workers,” former NLRB chairman and current Georgetown Law professor Mark Pearce told CNBC. “The vulnerable workers — they were not only scared, they were pissed.”

Emboldened workers willing to rock the boat

“Workers see a lot of opportunities,” Guy Berger, principal economist at LinkedIn, told the Washington Post last year. “Unless the labor market cools off a lot, there’s going to continue to be a lot of workers demanding collective bargaining power.”

Labor analysts also noted cultural and generational influences. Workers in some of the most high-profile organizing efforts tended to be younger, more educated, and more politically liberal than in the past. Their discontent reflects a sense of unfulfilled expectations.

Those workers are in jobs “that are inferior to those they expected or aspired to get,” Ruth Milkman, a sociologist of labor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, told the Post. “…It’s highly significant and highly unprecedented.”

The movement for greater equality that gained traction during the pandemic has highlighted the potential for unions to help workers address historical inequities in compensation, hiring, and benefits.

Furthermore, activism has spread due to publicity around union campaigns at workplaces like Amazon and Starbucks amid the proliferation of social media and other digital channels that rapidly spread workers’ message. This has had a domino effect, inspiring workers at other companies.

Clouds on the horizon

Despite these positive trends, there is cause for some caution about labor’s prospects. Chief among them is the possibility of a weakening economy and labor market later this year. The U.S. Federal Reserve has raised interest rates sharply in an effort to tame inflation and appears committed to continuing to raise rates to bring inflation back down to its target of 2% per year, on average. Some forecasters believe this could trigger a recession, which would in turn loosen the tight labor market and reduce worker leverage.

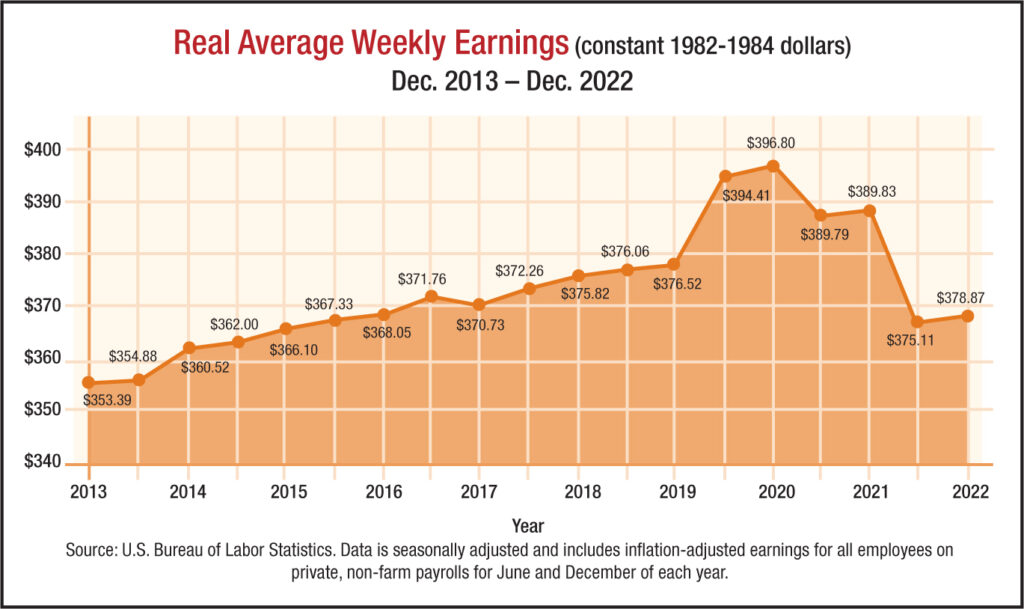

Organizers also point out that increased activism has not yet borne concrete progress in some areas. While wages have risen, especially for the lowest-paid workers, government data show that wages as a whole have not kept pace with inflation. The strongest wage gains appear to be driven not by concessions by one’s current employer, but by quitting a job and finding a new employer that will pay more. Data show that wage growth was strongest by those changing jobs. American families are facing the most severe cost of living squeeze in a generation.

Analysts also note that recent growth in union membership has not reversed a 40-year decline in unionization rates. Unions added 273,000 members in 2022, the biggest gain since 2015, but the percentage of American workers belonging to a union fell to 10.1% in 2022, the lowest since record-keeping began. This reflects faster growth in non-union employment compared to union jobs.

Finally, analysts say that if the labor market was as tight as official numbers show, workers would have more negotiating power and unions would be seeing an easier time at the bargaining table. This is borne out in the experience of UWUA locals. In recent months, many reported achieving record wage gains in contract bargaining, but the consensus is that the negotiating process has been just as difficult as in prior rounds.

Bottom line

While economic conditions favorable to labor last, unions should keep working to take advantage of the moment to organize new members and lock in contract gains that will carry members through any coming economic downturns.